In 2025, Prof. Jun Wan’s team at Wuhan Textile University published more than 20 peer-reviewed papers, reflecting a year of sustained output across electrocatalysis, functional fibers, thermal photonics, and extreme-condition energy systems. From this broader body of work, the team curated ten particularly novel and engaging studies that read less like isolated publications and more like a single, layered storyline. The plot is straightforward but technically demanding: modern energy and wearable systems increasingly have to operate where conventional materials fail, including corrosive seawater electrolytes, repeated bending and wet–dry cycling, large-area textile platforms, and extreme low-temperature environments. Across these regimes, mainstream solutions often share a structural weakness, improving one metric at the expense of another because material phases, interfaces, and radiative pathways are difficult to tune without sacrificing stability or manufacturability. The 2025 “Top 10” selection addresses this challenge through a consistent philosophy: non-equilibrium processing is used to unlock unconventional phases and architectures, and these microscopic advantages are then translated into device-level reliability by engineering interfaces, fibers, and radiative structures that remain functional under practical constraints. Together, the ten papers form a coherent progression across length scales, moving from crystal symmetry and orbital hybridization to porous nanosheets, coaxial fibers, textile-scale radiative management, and finally printable architectures for harsh-environment energy devices.

Act I. Opening the “phase-locked” materials toolbox with non-equilibrium synthesis

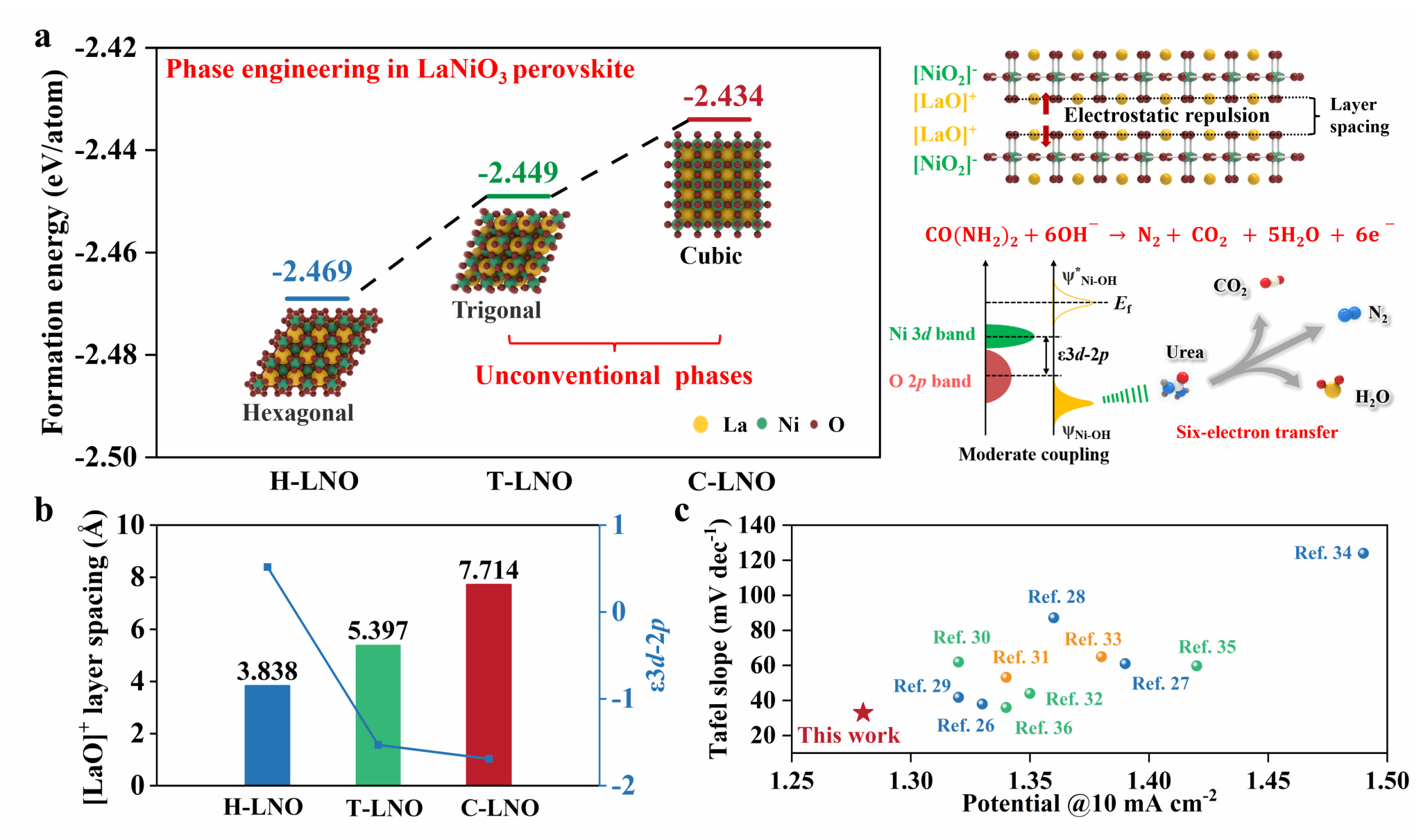

Many catalytic oxides and functional ceramics are “phase-locked”: they are thermodynamically stable, which is precisely why phase engineering becomes hard. Yet phase is often the fastest route to change electron transport, active-site geometry, adsorption energetics, and multi-electron kinetics. Paper 1 tackles this bottleneck head-on by demonstrating phase engineering in 2D LaNiO3 perovskite using a strongly non-equilibrium microwave-shock route (Figure 1). The work does not treat phase as a label; it treats it as a kinetic lever. By inducing selective phase transitions and rapid quenching while preserving a porous 2D structure, the study links symmetry and interlayer openness to faster charge transport and improved access to active sites in the six-electron urea oxidation reaction. A key signal of the improved kinetics is a low Tafel slope (33.1 mV dec-1), consistent with accelerated rate-determining steps enabled by the cubic configuration. This “phase unlocked without structural collapse” theme becomes a recurring motif in the rest of the portfolio: non-equilibrium processing is not an end in itself, but a way to access states that conventional thermal routes either cannot reach or cannot retain.

Figure 1. Structural features and performance-optimization mechanisms of distinct LaNiO3 phases. (Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2025, 64, e202413932.)

Act II. Making electrocatalysis realistic: seawater, alkaline conditions, and universal routes to activity

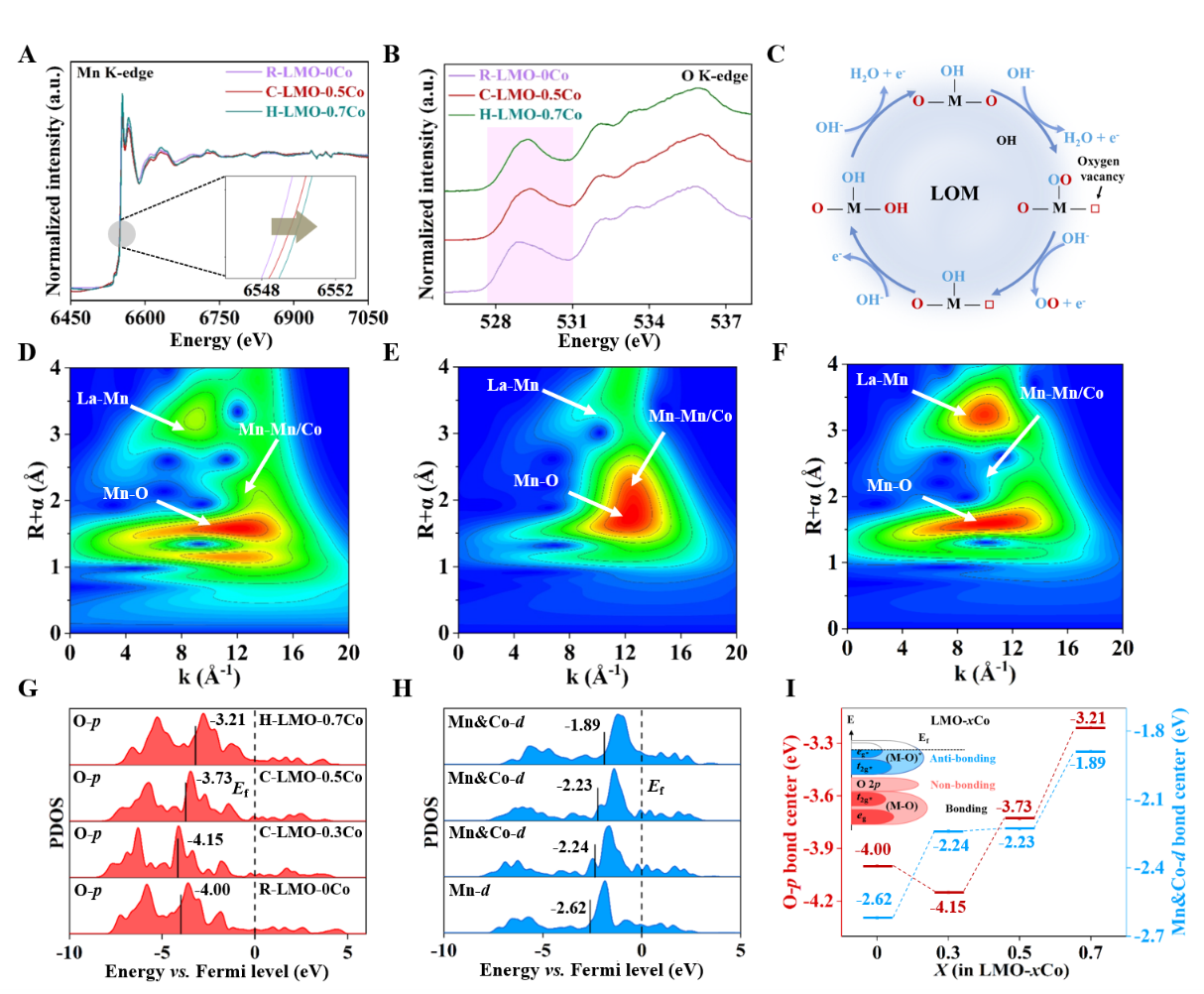

Catalysis that looks good in idealized electrolytes often fails under realistic conditions. Seawater electrolysis, for example, is attractive for green hydrogen, but oxygen evolution becomes sluggish and the saline environment intensifies stability challenges. The team addresses this gap with two complementary phase-engineering studies that deliberately target “hard-mode” operation. Paper 2 advances metastable cubic 2D LaMnO3 as a seawater-relevant oxygen evolution catalyst (Figure 2). The paper frames the problem precisely: seawater electrolysis needs catalysts that keep high activity in saline, alkaline environments where kinetics and durability are both penalized. By leveraging an unconventional cubic phase within a 2D architecture, the catalyst reaches 293 mV overpotential at 10 mA cm-2 with a 68.7 mV dec-1 Tafel slope in conventional OER testing. The work then pushes beyond standard benchmarks: in simulated seawater and real seawater, Tafel slopes of 71.1 mV dec-1 and 99.0 mV dec-1 are reported, and the system sustains operation over 100 hours at 400 mA cm-2, emphasizing that “high current and long duration” matters as much as low-overpotential snapshots.

Figure 2. Electronic Structure and Catalytic Mechanism of 2D LaMnO3. (Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2025, 74, 228.)

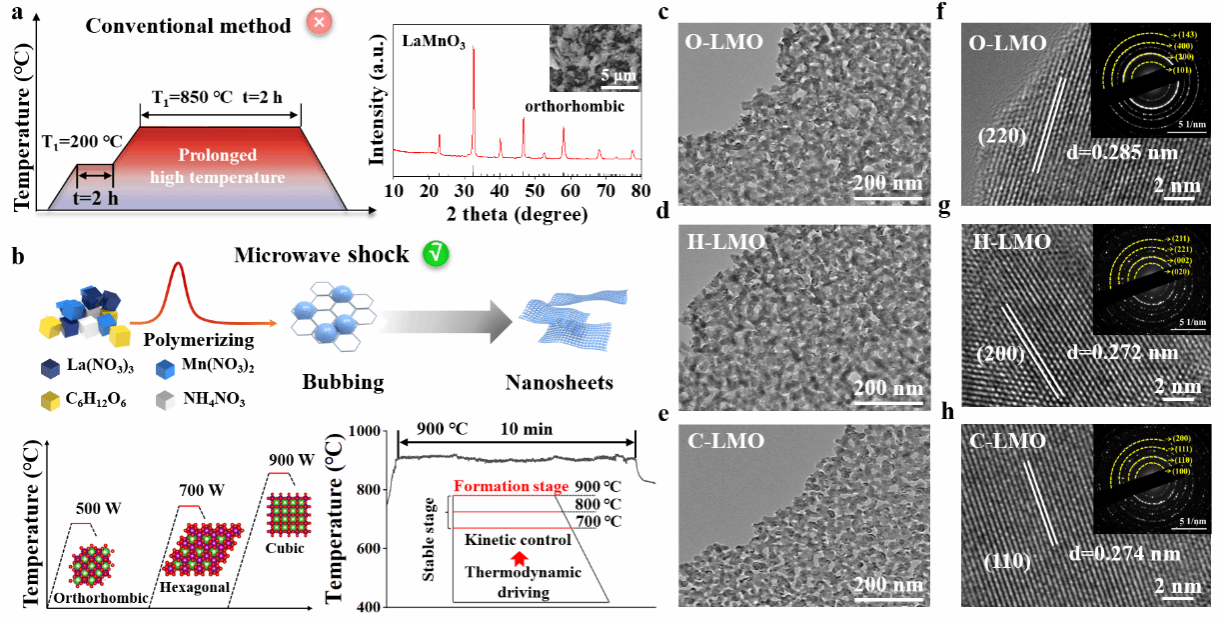

Paper 3 revisits the same core goal, efficient OER, through a synthesis lens that is explicitly designed to bypass thermodynamic barriers (Figure 3). Using microwave shock-driven thermal engineering, the study rapidly fabricates cubic-phase LaMnO3 nanosheets while maintaining porous 2D morphology, and reports 290 mV overpotential at 10 mA cm-2 with a 66.21 mV dec-1 Tafel slope in alkaline media. The significance is not repetition; it is reinforcement: the 2025 portfolio shows that the team is building a generalizable playbook for stabilizing unconventional phases in 2D perovskites.

Figure 3. Microwave-driven phase transition in LaMnO3 with preserved 2D architecture. (Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2025, 13, 31002.)

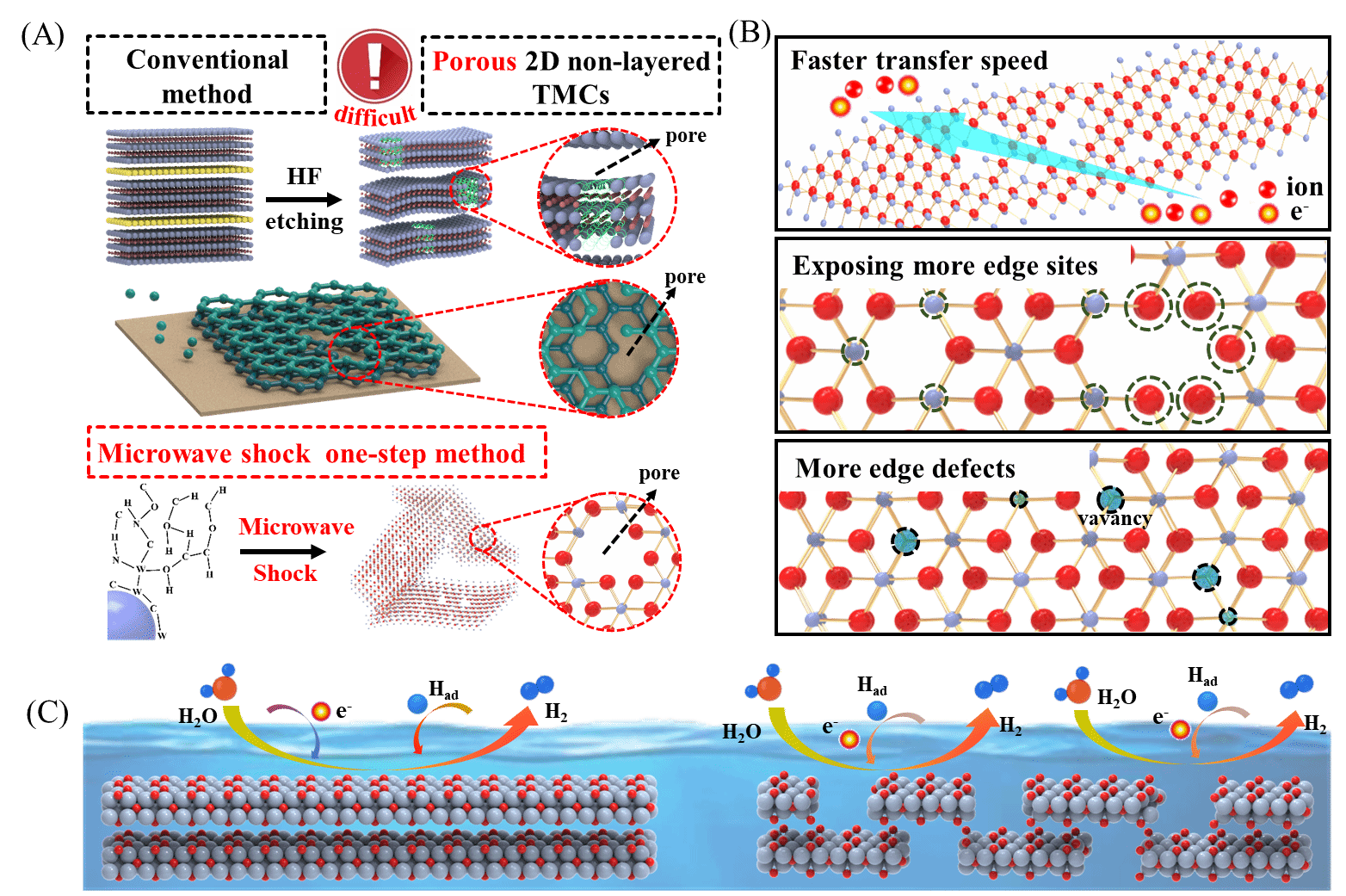

Completing the realistic-electrocatalysis arc, Paper 4 moves from OER to hydrogen evolution and answers a different practical question: can one achieve high HER activity in both acid and base without relying on layered templates? The paper introduces porous 2D non-layered transition-metal carbides created by microwave shock, positioning topology and porosity as decisive for exposing active sites and enabling fast kinetics (Figure 4). The resulting 2D porous W2C shows 48 mV overpotential in acid and 92 mV in base at 10 mA cm-2, with Tafel slopes of 43 mV dec-1 and 54 mV dec-1, respectively. Importantly, the work presents a route that can be extended to other carbides (for example Mo2C, NbC, TaC), aligning performance with synthetic universality. Together, these electrocatalysis papers deliver a clear story: phase and topology engineering become credible only when they translate into activity and durability under realistic constraints, including seawater-relevant environments and dual-acid/base HER operation.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of the synthesis challenges for porous 2D non-layered transition-metal carbides. (SusMat 2025, 5, e252.)

Act III. From catalysts to fibers: interface physics as the bridge to flexible energy and underwater sensing

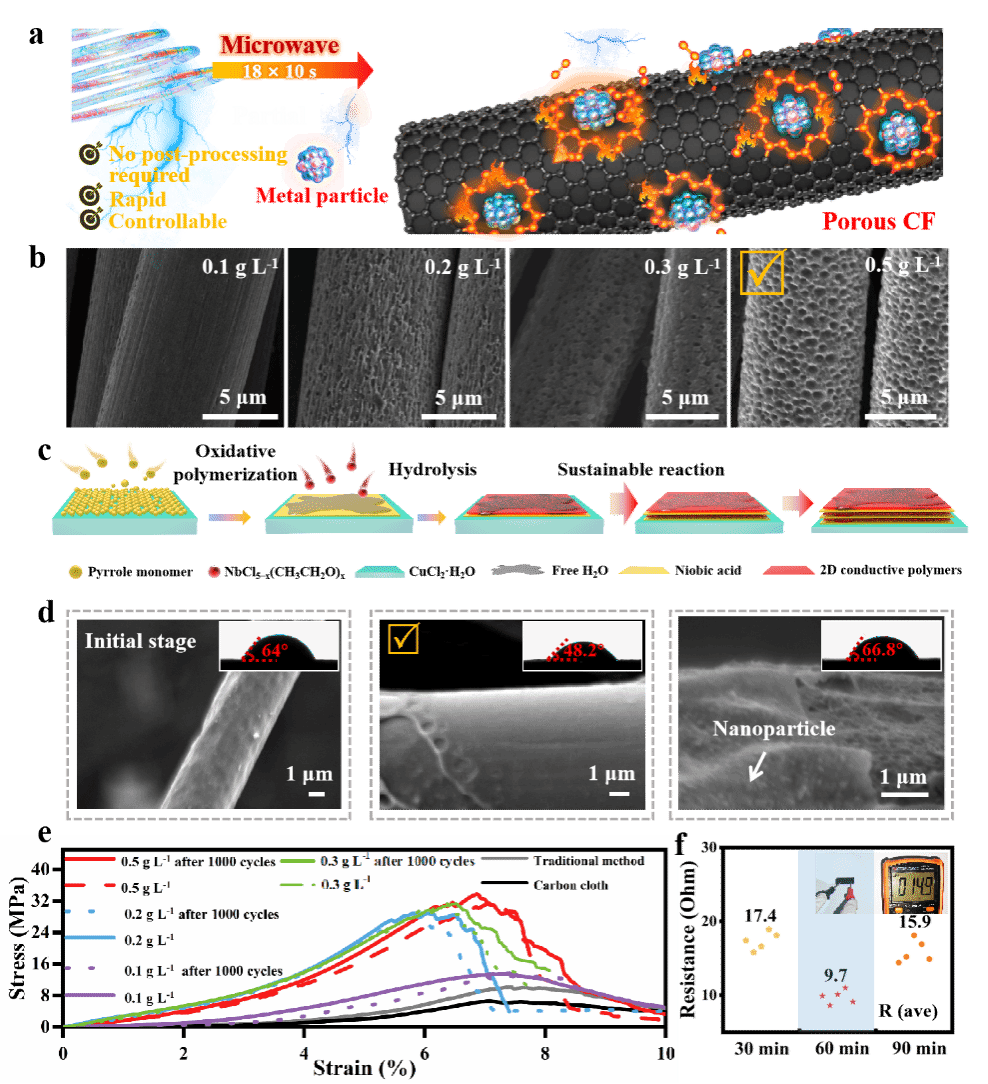

Electrochemical activity alone does not build wearable technology. Once materials are integrated into fibers, devices live or die by interfaces: adhesion, stress transfer, electrolyte accessibility, and resistance stability under deformation. Two 2025 papers show how the team translates nanoscale design into fiber-level reliability. Paper 5 confronts a persistent failure mode in fiber-based energy storage: carbon fibers are mechanically robust but physically smooth and chemically inert, which makes electroactive coatings prone to delamination during bending (Figure 5). The study introduces horizontally oriented 2D “skin” structures grown on the fiber interface, forming a bamboo-sheath-like architecture that maximizes interfacial binding and charge transport pathways. The resulting flexible device achieves an areal capacitance of 1730.45 mF cm-2 and demonstrates long-life cycling behavior, including 88.06% capacitance retention after 5000 cycles, alongside an extended lifespan reported up to 10,000 cycles. The message is device-relevant: stability is not treated as an afterthought but engineered into the interface geometry.

Figure 5. Regulation of fiber skin performance by porous architecture and 2D layer thickness. (Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 509, 161557.)

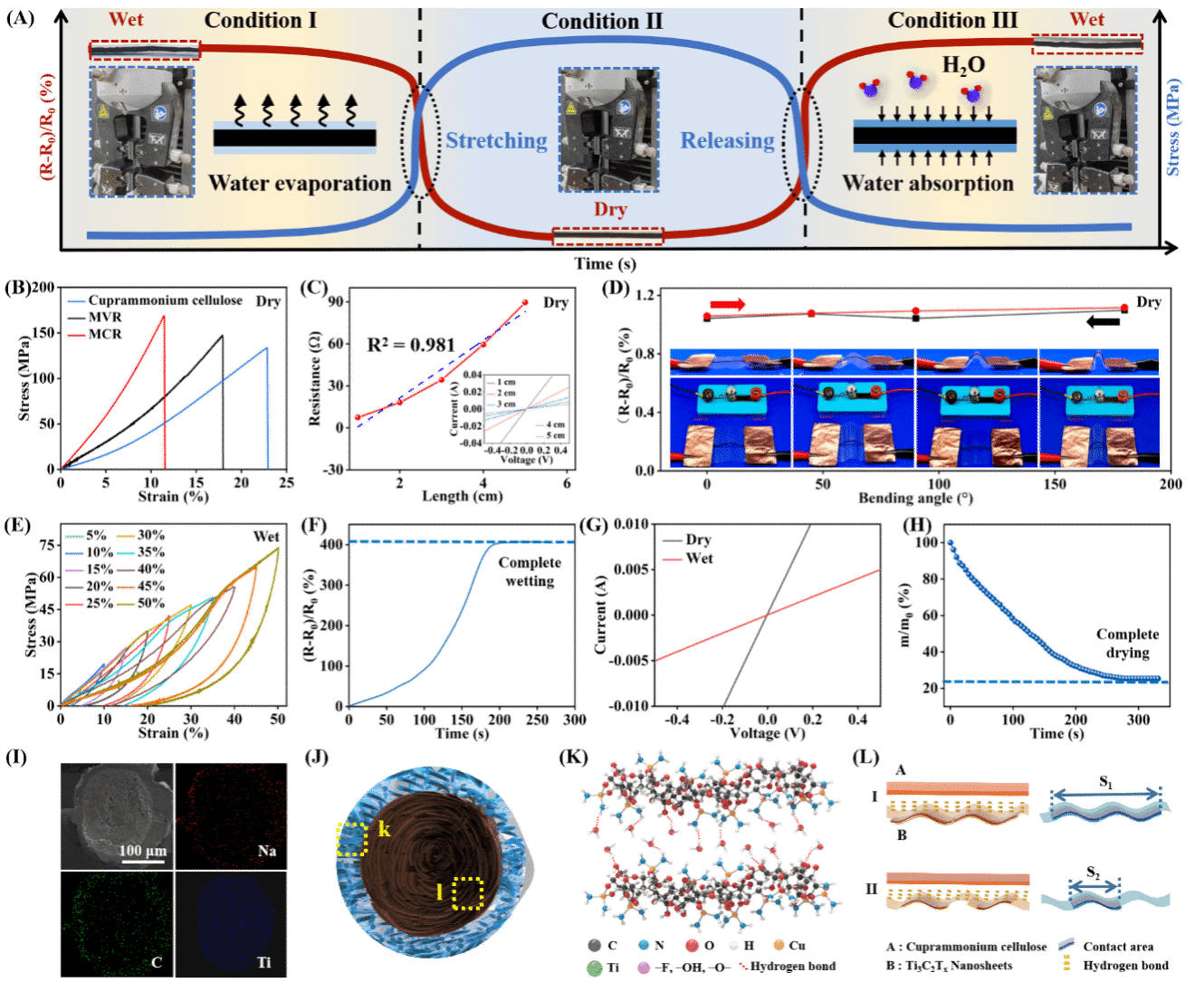

Paper 6 extends this interface-driven design philosophy into underwater electronics, where the challenge is even less forgiving: strain sensors must operate in water, but water usually disrupts conductive networks and induces mechanical degradation. The study reports a durable coaxial fiber-based underwater strain sensor that relies on a reversible dry–wet transition instead of a simple “water-repellent” strategy (Figure 6). The results are framed around recoverability: in dry conditions, tensile strength reaches 169.8 MPa, while in wet conditions it remains 73.6 MPa, still substantial for fiber devices. The sensor demonstrates a gauge factor up to 20.2, and its electrical behavior is designed to be reversible: resistance stabilizes after about 200 s during immersion, and returns to its initial state within approximately 300 s upon drying. This converts the wet–dry cycle from a degradation pathway into an operational mode, enabling realistic marine or amphibious sensing scenarios. At this point in the story, the scale has shifted: unconventional phases and porous nanosheets are no longer only about catalytic metrics, they become the foundation for flexible, durable, and application-stable fiber systems.

Figure 6. Electrical and mechanical performance of the MCR sensor under dry–wet cycling, with interfacial stability verification. (InfoMat 2025, 7, e70030.)

Act IV. Managing heat as radiation: from printable cooling layers to mid-infrared textiles and low-temperature device architectures

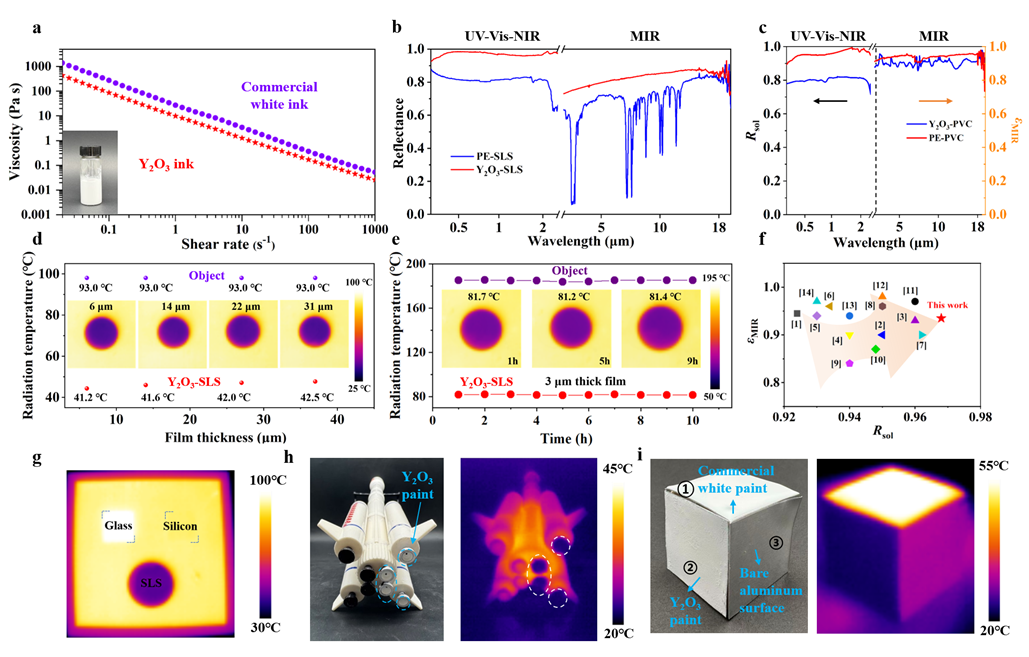

The last four papers broaden the narrative from electrochemistry to thermal photonics and manufacturing, but they preserve the same logic: performance is governed by structure, and structure must be scalable. Paper 7 targets passive radiative cooling with a nuanced materials insight (Figure 7). Many cooling stacks require a top layer that is highly reflective in the solar band while remaining transparent in the mid-infrared so the substrate can radiate heat effectively. Polyethylene is MIR-transparent but its solar reflectance is limited. The paper introduces microwave-engineered 2D Y2O3 to achieve near-unity VIS–NIR reflectance (RVIS–NIR = 0.97) while maintaining high MIR transparency (τMIR = 0.94). In steady-state tests on a representative stack, the bottom temperature stabilizes at ~16.98°C, which is 3.75°C lower than a PE-based counterpart, 5.5°C lower than ambient, and 20.62°C lower than the bare substrate. The work also emphasizes manufacturability through printable inks, signaling that radiative cooling is being treated as an engineering system, not a laboratory curiosity.

Figure 7. Optical performance and process compatibility of 2D Y2O3 coatings. (Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2025, 13, 39330.)

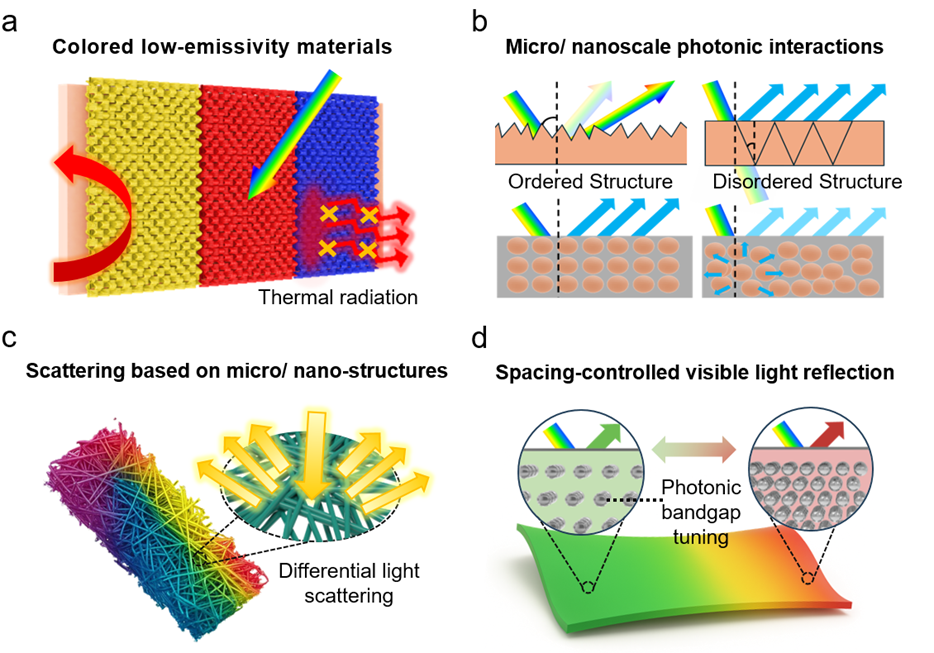

Paper 8 then reframes low-emissivity design in a way that is especially relevant for aerospace and camouflage: most studies chase εMIR reduction without integrating visible optics. This review proposes a structure–property–optics framework that classifies low-εMIR materials by their visible-light behavior into opaque, transparent, and colored categories, elevating “what a surface looks like” from aesthetics to functionality (Figure 8). The practical implication is immediate: a low-emissivity surface that fails visible requirements cannot serve camouflage or multifunctional envelopes, no matter how good its εMIR value is.

Figure 8. Schematic illustration of the structures and mechanisms of color-tunable low-emittance mid-infrared materials. (Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2025, 13, 39330.)

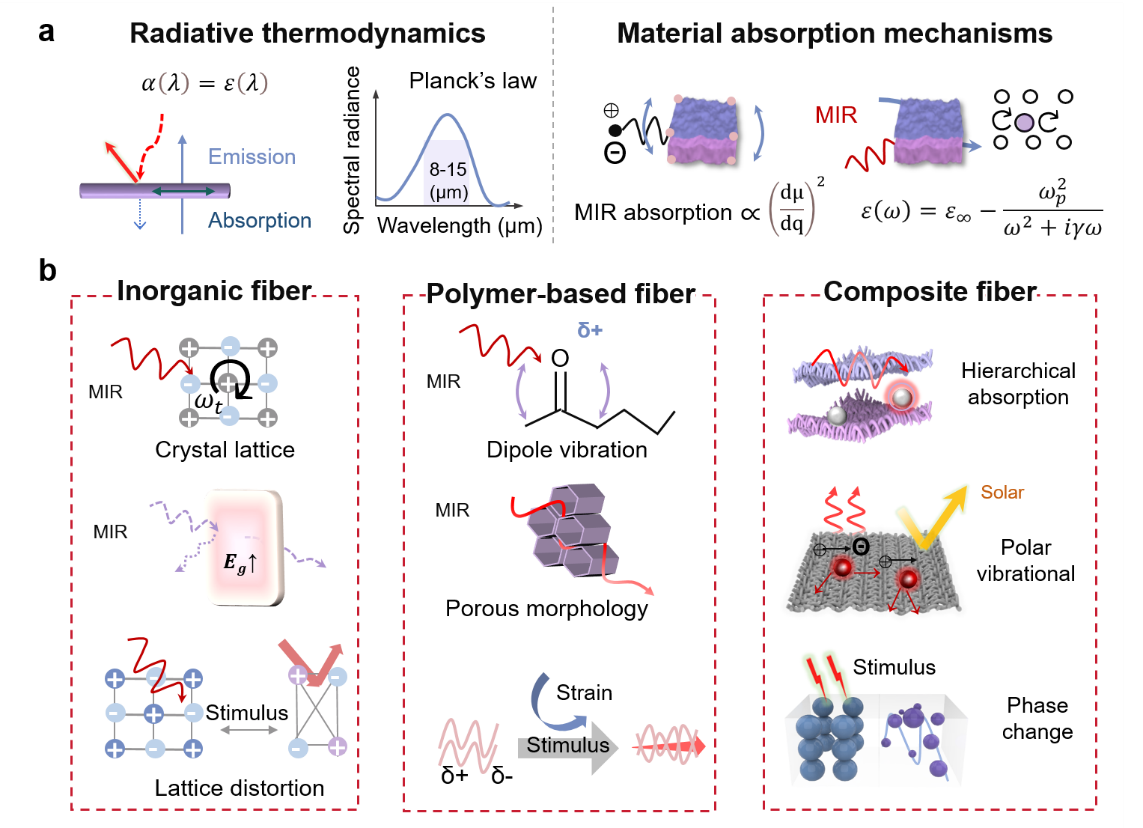

Paper 9 carries the thermal narrative into textiles, where comfort and protection depend on controlling radiation rather than only blocking conduction (Figure 9). The review argues that MIR thermal management textiles work because over 90% of human thermal radiation lies in the MIR, but the field often lacks a unified material–structure view. It therefore organizes MIR-responsive fiber materials (inorganic, polymer-based, composite) and then connects them to structural strategies, layered optical structures, surface finishing, and weave design, so that spectral selectivity and multi-scale heat transport can be engineered together.

Figure 9. Schematic illustration of mid-infrared thermal management principles and material classification. (Small 2025, 21, e09257.)

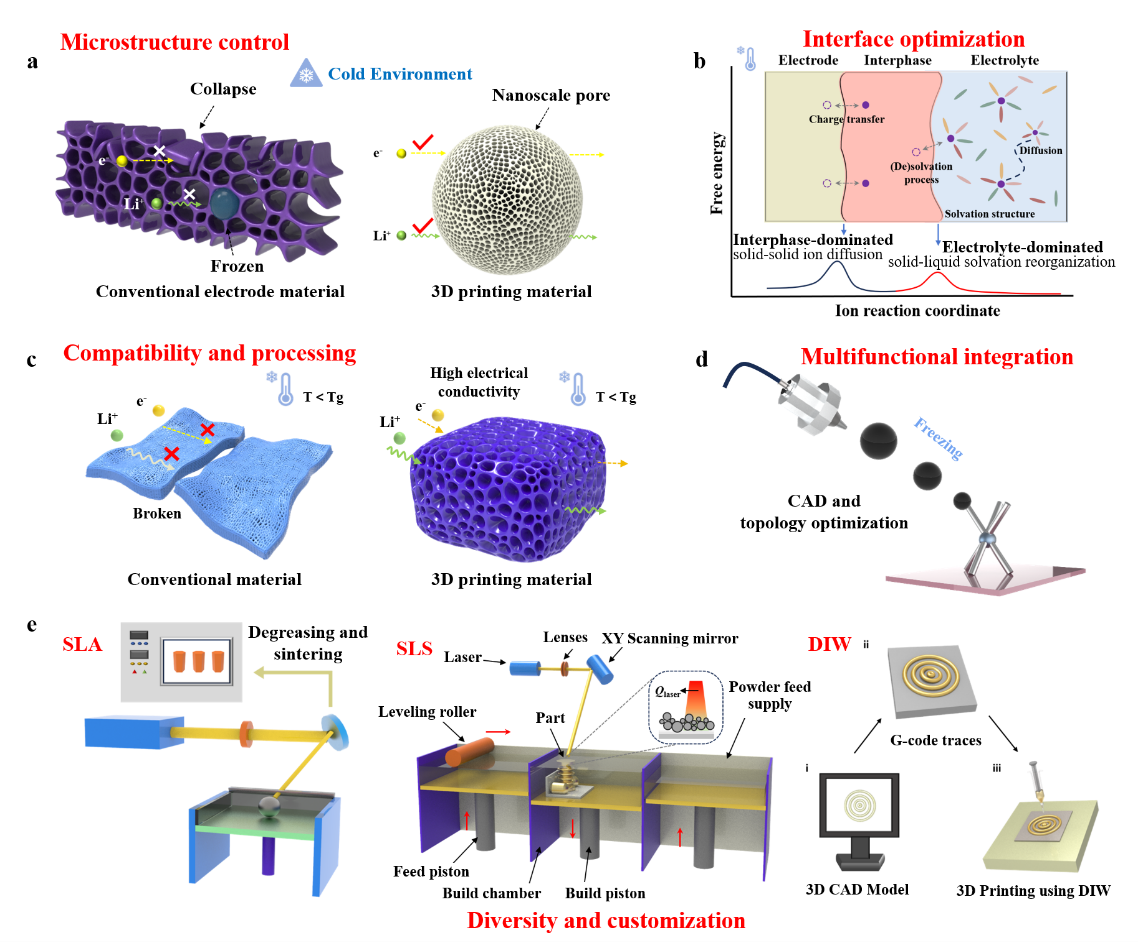

Finally, Paper 10 closes the 2025 arc by linking harsh-environment performance with manufacturing logic. Extreme low-temperature energy storage suffers from electrolyte freezing, slowed interfacial kinetics, and microstructural instability (Figure 10). This review positions 3D printing as a route to address those bottlenecks through microstructural control, multifunctional integration, and interfacial optimization, while being candid about what remains unresolved: mechanisms for low-temperature optimization, printability of relevant materials, and the need to integrate materials, processes, and device design into a coherent system.

Figure 10. Advantages of 3D printing for low-temperature energy storage. (Virtual and Physical Prototyping 2025, 20, e2459798.)